It’s hard to imagine life without her in it. She was a constant from the moment I was born

until this week when she died. I sat at

her funeral in the church to which she belonged all but the first eight years

of her life and felt more than I thought, listened to my body’s own fullness

more than cogitated her absence. Words

are of little use at the moment of seismic change.

And the death of Kathryn Cherry Lundy, my cousin “Tat,” was

just such a moment.

Now, however, words are coming, borne on the wings of

memories. Here is one. On a May day in 1955, I was with her little

girls Suzanne and Jo together with some neighborhood kids in the yard next door

to the Lundys' house. A boy more

adventurous than careful, I went in search of a dead snake to identify it. Four or five steps into the canebrake and I

looked down and saw the object of my search—under my right foot. The copperhead

wasted no time, once I'd removed my foot from his head, in striking my ankle, sending

me into paroxysms of sheer terror.

Hearing the commotion, Tat came to see what was the matter.

She quickly retrieved from the ironing she was doing one of Lloyd's

handkerchiefs, tied a tourniquet around my leg, called my mother at work,

crammed me and the other kids into the car, and got me to the old Conway

Hospital in probably no more than 10 minutes, picking up Mama along the way.

It's not too much to say that she saved my life that day with her quick

thinking and calm response.

|

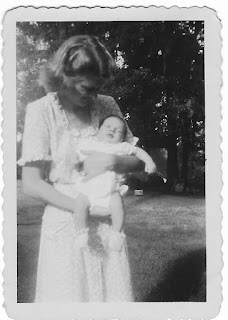

| Tat and I |

She could be that

way: no nonsense, yet compassionate;

funny yet reliably steady; firm yet imminently approachable. Here she is in a photo taken when she, a senior in high school,

held me, a newborn probably only days old.

I came into her life just a short while before she left for Winthrop

College. One of the first really big

trips I made was with Aunt Myra to see her graduate from college—the first

Burroughs grandchild to do so. I

strained to see her walk down the aisle at Kingston Presbyterian Church to wed

Lloyd a couple of years later, went multiple times out to Jordanville to meet

and play with her new Lundy relatives, picked beans and shelled peas with her

in the summer. I even have a few

memories of aggravating her, as when I wandered into her house weeks before her

marriage and took it upon myself to rearrange her gifts that she'd carefully

laid out in the dining room. She brooked no foolishness of that sort.

Years went by and my visits to Conway were sparse. Time came

when my mother was dead and my father was living in a skilled care facility. When I'd visit, her house became the place

where I was always welcome, always well fed, and treated to conversations in

which I would sometimes turn over her tickle-box when I imitated various

relatives. There were many subjects we

never discussed, and to this day I never knew her opinions on a variety of

hot-button issues. But there was one position that I knew well firsthand, and

that was how accepting and inclusive she was.

Having a gay cousin seems not to have crossed her mind until on one

visit I told her she had such a one. She

neither sat in silence nor rushed to gush over me nor uttered a word of

disapproval or disavowal. From that day

forward, her home and heart were open to me and anyone who happened along with

me. I rather doubt that I was anywhere

near an exception to any rule. She knew

how to practice hospitality, which, after all, was the broadest, most creative,

most limit-challenging ministry that Christ ever had. And, to her credit, while we chatted a bit

from time to time about religion and my vocation in it, she never invoked to me

a religious reason for doing anything.

She just did what she did because it was the right thing to do.

She was more than a cousin. She was a sister. The only one I've ever had. And I couldn't have had a better.

May 13, 2018

No comments:

Post a Comment